Jews of Azerbaijan have played an important role in the centuries-old history of our country. Various groups such as Mountain Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Georgian Jews showcase the richness of Azerbaijani culture. Synagogues and Jewish communities located in regions like Quba, Oghuz, and Baku offer tourists a unique historical and cultural heritage. Azerbaijan's tolerant and multicultural environment ensures that Jewish communities continue to live today in peace and harmony.

Located at the crossroads of cultures and continents, Azerbaijan has attracted numerous tribes and peoples since ancient times. Some merely passed through along the Silk Road, while others settled here, and today more than 20 national minorities live peacefully in Azerbaijan. Among them are Jews, who have preserved their unique culture and traditions for centuries, including their religion, languages, and worldview. Studying their heritage means exploring a millennia-old history and discovering a unique example of peaceful coexistence.

Today, Azerbaijan is home to three ethnic subgroups of Jews: Mountain Jews (Juhuro), Ashkenazi, and Georgian Jews. In the southern regions of Jalilabad and Lankaran, small numbers of Subbotniks and Ger – ethnic Russian groups practicing Judaism – can also be found.

Jewish heritage in Azerbaijan is represented by monuments spread across areas such as Baku, Quba, Oghuz, Ismayilli, and others. Many ancient synagogue ruins have been found throughout the country, while seven synagogues are still active today.

Throughout history, Azerbaijan has hosted various peoples, including Jews. Azerbaijani Jews are divided into groups such as Juhuro (Mountain Jews), Ashkenazi, and Georgian Jews. The country also hosted Crimean Karaites, Kurdish Jews, Bukharan Jews, and non-Hebrew Subbotnik and Ger Jews for some time. Currently, the Jewish population in Azerbaijan is approximately 1,200, the majority being Mountain Jews.

Jews mainly reside in Baku, Sumgayit, Quba, and Oghuz districts. Krasnaya Sloboda is the most densely populated area of Mountain Jews worldwide. After 1920, almost no Jewish families remained in Shamakhi district. Another area where Jews have lived is Goychay, where they settled at different times in Azerbaijan, but now only a few families remain. Oghuz district is among the places with the largest Jewish population, and there is even a settlement called the Juhuro Quarter. Two major synagogues are active in this area. Previously, Jews lived in the Mujju-Haftar region of Ismayilli, where a Jewish cemetery still exists today. Additionally, Jews settled in Yevlakh, Barda, and Shirvan regions, but after a certain period, no Jews remained there.

The history of Jews living alongside Azerbaijani Turks stretches back centuries, even before the Albanian state. Azerbaijani researcher Mohammadhasan Velili (Baharly) wrote in his 1921 book published in Baku, “Azerbaijan. Geographical-Natural, Ethnographic and Economic Considerations”:

“Azerbaijani Jews are the descendants of ancient Jews captured by the Assyrian kings, who lived first in Assyria, then in Media. After the fall of Assyrian rule, during the reign of King Shalmaneser, they migrated to present-day Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Dagestan.”

According to some studies, the formation of the Jewish diaspora in Azerbaijan is associated with the Achaemenid period. Archaeological excavations near Baku revealed a 7th-century Jewish settlement, and an old synagogue was found 25 km southeast of Quba.

The first religious building in Baku was constructed in 1862 and converted into a synagogue in 1896. By the late 19th century, several new synagogues were built, and in 1910 the first constructed synagogue in Baku was inaugurated. By the late 19th century, Baku under Russian occupation had become one of the centers of the Zionist movement. The “Hovevei Zion” organization was established in 1891, and the first Zionist organization was formed in 1899. This movement remained strong during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic period. In 1919, the Jewish People’s University was opened, and intermittently schools in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Juhuri, as well as charitable organizations and cultural centers, operated.

During the Soviet period, Jews, along with Azerbaijanis, faced repression. All Zionist activities and Hebrew resources were banned. In the early 1920s, several hundred Mountain Jewish families emigrated from Azerbaijan and Dagestan to Israel. In the 1970s, after the lifting of migration restrictions, many Jews moved to Israel. In 1970, the Jewish population in Azerbaijan was 41,288, of which three thousand emigrated to Tel Aviv and Haifa between 1971–1978.

Jewish Footprint in Azerbaijan – Mountain Jews

The exact origin of Mountain Jews is unknown. Historians believe they first arrived in Azerbaijan in the 6th century, expelled from Mesopotamia for attempting to leave the Sasanian Empire.

In the mid-18th century, Mountain Jews settling in various regions were invited to Quba by the rulers of the Quba Khanate and established their own Jewish villages. Since 1926, this area has been known as Krasnaya Sloboda or Red Village. They engaged in crafts such as carpet weaving and leatherwork, as well as agriculture, viticulture, and animal husbandry. Mountain Jews call themselves Juhur and speak Juhuri, a Judeo-Persian language.

Another center of Mountain Jews in Azerbaijan is Oghuz, although most migrated after the collapse of the USSR. They also live in the village of Mujju in Ismayilli district, where significant Jewish heritage is preserved.

History and Settlement of Mountain Jews in the Caucasus

Mountain Jews are believed to have lived in the Caucasus for many centuries. According to historical sources, one of the lost ten tribes exiled by Assyria in 722 BCE later migrated from Southwestern Iran to Dagestan under pressure from the Achaemenids and Sasanians.

Some theories suggest Mountain Jews came from Iran or the Byzantine Empire during early medieval times due to Arab invasions. Jews settled on the left bank of the Kura River in Albania and had contact with the neighboring Kipchaks and the Khazar Khaganate.

Due to close ties with the Khazar Empire, Judaism was declared the state religion of the Khazar state in 790. Jews living under oppression settled in the newly formed Khazar Khaganate. By the late Middle Ages, Gilan Jews established economic and cultural relations with local Jews. Until the Soviet era, they were engaged in silk production and textile trade.

In 1730, under the decision of Quba Khan Huseyn Ali, Jews became landowners. According to the 1926 Soviet census, more than 10,000 Jews in the country were Mountain Jews. In the late Soviet period, the exact number was unknown as they identified as Tat to avoid anti-Semitic pressure. Some researchers dispute the theory that Tat and Mountain Jews share the same origin.

Today, Mountain Jews form the main part of the Jewish diaspora in Azerbaijan. They speak Juhuri, considered the Judeo-Tat dialect of the Tat language, sometimes called Jewish Tat.

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews refer to Jews from Central and Western Europe, including Poland, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Germany, and Hungary. They first arrived in Baku in the early 1800s. Due to continuous migration, by 1910 the Ashkenazi Jewish population exceeded that of Mountain Jews. Many settled in oil-rich Baku. One of the leading oil companies of the Russian Empire, “Caspian-Black Sea,” was founded by the German-Jewish Rothschild family.

Ashkenazi Jews continued migrating to Azerbaijan until the late 1940s. Many of them were Jews from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus displaced during World War II.

Ashkenazi Jews were active in Azerbaijani politics. For example, Dr. Yevsei Gindes from Kiev was appointed Minister of Health of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. His contributions to medicine at the time were significant. Ashkenazi Jews participated in the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, supporting locals and resisting foreign occupiers.

According to data recorded in 1912, one-third of lawyers and doctors were Jewish. During the Tsarist and Soviet periods, most Ashkenazi Jews became Russified due to migration. However, they also tried to speak Azerbaijani fluently. The number of Yiddish speakers is unknown.

Today, Ashkenazi Jews form the second-largest Jewish community in Azerbaijan after Mountain Jews. One Ashkenazi synagogue operates in Baku.

Gers and Subbotniks

Gers and Subbotniks are ethnic groups from various regions of Russia who adopted Judaism in the 1820s. Between 1839–1841, the Tsarist government exiled them to the South Caucasus, mainly to Azerbaijan. Upon arrival, they were settled in the village of Privolnoye in Jalilabad, one of the largest settlements in the area, previously called Hashtarkhan-Bazar. Later, Privolnoye became one of the largest Jewish-Russian settlements in Russia. By the late Soviet period, the Gers and Subbotniks population in Azerbaijan was approximately 5,000. By 1997, only 200 remained, most having moved to Russia, and currently, Gers and Subbotniks no longer reside in Azerbaijan.

The Subbotniks and Gers are closely connected groups that emerged in 18th-century Russia as part of a spiritual Christian movement. Observing the Sabbath, these groups believe in refraining from work and worldly discussions on that day. Considered "heretics" by Imperial Russian officials and Orthodox clergy, the Subbotniks and Gers were persecuted, isolated, and eventually resettled in the early 19th century. Some settled in the Jalilabad region of southern Azerbaijan, creating villages like Privolnoye, which today hosts only a few Subbotniks continuing Jewish traditions.

Other Jewish Groups in Azerbaijan

One of the main Jewish groups in Azerbaijan is the Ebraelis, also known as Georgian Jews. They first arrived in Georgia after the conquest of Jerusalem in 586 BCE and the destruction of the First Temple by Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II. The Ebraelis, who lived in various regions of Georgia, adopted many Georgian customs and traditions. For economic reasons, a small group migrated to Baku in the early 20th century, strictly observing Jewish religious practices while preserving Georgian traditions. They worked as merchants and craftsmen, becoming partners in major Russian-Caucasian trade houses, stock exchanges, commercial banks, and joint-stock companies. Today, the Ebraeli community in Baku has around 300 members.

Before the Tsarist era, the relationship of local Jewish communities with Georgian Jews is unclear. However, by the 1910s, the presence of Georgian Jews in Baku and a related educational center was documented. Today, a few hundred Georgian Jews live in Azerbaijan, with a synagogue in Baku serving them.

Kurdish Jews, who spoke Jewish Aramaic, began migrating to Azerbaijan in 1827, with some coming from southern Azerbaijan and Iran. From 1919 to 1939, a Kurdish synagogue existed in Baku. During the Soviet era, the Stalinist government deported Kurdish Jews from the Caucasus and Azerbaijan in 1951.

The Karaim Jews (Crimean Karaites) are descended from the Khazar Turks, numbering only around 5,000 worldwide. In 1989, there were 41 Karaim Jews and 88 Bukharan Jews in Azerbaijan. These groups no longer live in the country.

The Gers and Subbotniks are ethnic groups that adopted Judaism in the 1820s in various regions of Russia. Between 1839 and 1841, the Tsarist government exiled them to the South Caucasus, primarily to the village of Privolnoye in Jalilabad. This settlement later became one of Russia's largest Jewish-Russian communities. By the late Soviet period, the Gers and Subbotniks numbered around 5,000 in Azerbaijan, but by 1997 only 200 remained. Today, most have emigrated to Russia, so Gers and Subbotniks no longer live in Azerbaijan.

Jews in Modern Azerbaijan

During the Soviet period, Azerbaijani Jews, like other minority peoples, could not freely practice their religious and cultural life. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the establishment of independent Azerbaijan, the Jewish community gained religious and cultural freedom. The Azerbaijani state created conditions for Jews to preserve their religion and culture alongside other minority groups.

Jewish communities have lived in Azerbaijan for centuries and consider it their homeland. A notable example is Azerbaijani National Hero Albert Agarunov, who died in the Karabakh war. Azerbaijani Jews live in peace and security, actively participating in economic, political, and social life.

Currently, three Jewish communities operate in Azerbaijan: Mountain Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Georgian (Ebraeli) Jews. There are three synagogues in Baku serving these communities. The Mountain Jews’ synagogue in Baku is the largest in the Caucasus. Near Quba, in Red Town, there are two synagogues; Oghuz also has two synagogues. The synagogue in Jalilabad's Privolnoye village for Gers closed in the 1990s due to population decline. The synagogue for Mountain Jews was built by order of President Ilham Aliyev.

Two Jewish schools operate in Baku, one under state supervision. Jewish language and culture are also taught in several universities. The Azerbaijani Parliament includes a deputy representing the Jewish community.

Azerbaijani Jews are active in promoting Azerbaijani realities both domestically and internationally. Azerbaijan maintains political, military, and economic cooperation with Israel. Jews play a key role in strengthening Israel–Azerbaijan relations and conveying Azerbaijani truths to the world.

This example represents true tolerance and multiculturalism, showing how Azerbaijani society enables all ethnic and religious groups to live together in peace and unity.

Baku and the Jewish Community

The Jewish population in Baku primarily consisted of Ashkenazim who began arriving in the 1830s. The oil boom and economic opportunities attracted more people, and by 1913 Jews made up 4.5% of the city’s population. Despite this, 30–40% of doctors and lawyers were Jewish. During the post-Soviet instability, many Baku Jews emigrated.

Synagogue of Ashkenazi and Georgian Jews

Synagogue of Ashkenazi and Georgian Jews

Located in Baku's old Jewish quarter, the Synagogue of Ashkenazi and Georgian Jews is one of the few synagogues built in this part of the world in the last century and is considered among Europe’s largest synagogues.

Its 2003 opening was a historic event for Ashkenazi and Georgian Jews. Previously, they had worshipped in a single-story building, separated by the Soviet government, with inadequate conditions.

Address: 171 Dilara Aliyeva Street

Phone: +99412 597 9190

Working Hours: Daily, 09:00 – 19:00

Mountain Jews’ Synagogue

The nearby Mountain Jews’ Synagogue has been active since 1945. At that time, an old building in the city center was allocated to Mountain Jews. Since the original building was unusable, it was demolished during the construction of the Winter Park, and a new building was constructed on the site. The new synagogue opened in 2011.

Architecturally, the building is remarkable and worth visiting.

Address: 72 Alimardan Topchubashov Street

Phone: +99412 596 7128

Working Hours: Daily, 09:00 – 19:00

Rashid Behbudov State Song Theater

Another important site is the building originally constructed in 1901 as Baku’s first synagogue, which today houses the Rashid Behbudov State Song Theater.

During the 1930s Soviet anti-religion campaign, the synagogue was closed. A few years later, the building was converted into the Jewish Workers’ Theater. After the theater was closed in 1939, the building served various purposes and has functioned as a Song Theater since 1980.

Address: 12 Rashid Behbudov Street

Phone: +99412 493 9415

Chabad Or Avner Educational Complex

This school was opened in 2010 in Baku's Khatai district to support the preservation of the unique culture and traditions of Azerbaijan’s Jewish community.

The school offers secondary education in Russian and Hebrew, teaching the basics of Jewish culture and traditions. The complex also organizes dance and music programs for Jewish tourist groups visiting Baku and provides kosher catering services to various regions of Azerbaijan.

Quba Red Town

A beautiful arched bridge from the 19th century spans the Gudyalchay River, connecting Quba with the Red Village, one of Azerbaijan's most unique settlements.

Considered the last living "shtetl" (Jewish settlement) in the world, the Red Village is entirely inhabited by Mountain Jews, with around 3,000 residents. Its name comes from the distinctive red tiles and stones used in house construction. Today, the 19th-century red-brick buildings and the grand mansions of wealthy residents form an intriguing mix.

What to see in the Red Village:

Heydar Aliyev Park: An ideal place for a peaceful walk. Old trees, tiered fountains, and beautifully decorated pathways await visitors. The teahouse in the park is especially popular among local elders. Here, you can not only drink tea but also meet friends, discuss news, and play backgammon.

Historical and cultural sites: The former Birth House, located in the village center, is of particular interest. The architecture of the green-colored building harmonizes with the surrounding scenery. Built at the end of the 19th century, it was granted local historical monument status in 2001. According to local legends, the building belonged to a wealthy Jewish merchant without children, who decorated it with murals of happy children.

Mountain Jewish Culture: You can visit the mikveh – a ritual bath for Jewish religious purification. This bath serves the local synagogues.

Gilaki Synagogue: Built in 1896 by local architect Hillel Ben-Hayyim, this synagogue was not closed even during the Soviet era. The building has 12 windows, symbolizing the 12 tribes of Israel. Under the wooden roof is a two-story octagonal bimah, which holds the main platform for reading the Torah.

Six-Domed Synagogue: Constructed by Hillel Ben-Hayyim in 1888. Its six-domed hexagonal design was a tribute to migrants who moved from Gulgat to the Red Village in six days, invited by Huseynali Khan.

Jewish Heritage in Quba

A building in the Red Village, before being restored and reopened as a functioning synagogue in 2001, was used as a warehouse.

One of the village's oldest cemeteries is located in the Gisori neighborhood on a steep hill. The oldest tombstone in the Gisori Cemetery dates back to 1807–1814. About 80 cm tall, these stones were made from local stone and inscribed with text. Other early 19th-century tombstones are simple rectangular stelae. Mid-19th-century stones feature simple rosette decorations, and later 19th-century stones are adorned with leaves and the Star of David.

When visiting the cemetery, do not miss the grave of Rabbi Gershon. He showed exceptional talent in learning the Torah from childhood. In 1853, after the death of his father, Rabbi Reuven, chief rabbi of the Caucasus, he took over the leadership of the community. Rabbi Gershon opened and led the first beth din (religious court) in Quba, the only one in the Caucasus. Under his leadership, 18 synagogues, yeshivas, and cheders (religious schools) were established, and the Red Village became known as the "Jerusalem of the Caucasus." Rabbi Gershon passed away in 1891, and his restored grave, renovated in 2013, continues to attract Mountain Jews from around the world.

Another interesting state-protected architectural monument in the Red Village is the Arched Bridge over the Gudyalchay River. Of the seven bridges existing in the Quba region between the 17th–19th centuries, only this one remains. Built in 1894 by Russian Tsar Alexander I to replace the old wooden bridge, it aimed to strengthen the Russian military presence in the Caucasus. The 14-arch brick bridge is 275 m long and 8 m wide. Its multi-arched design allows it to withstand floods and heavy currents without damage. Today, the bridge is only for pedestrians and offers a romantic view of the Red Village.

Next to the arched bridge is the Red Village Mountain Jews Restaurant. Here, you can enjoy local culinary experiences with a beautiful view of the Gudyalchay River. For example:

Geylo: a vegetable dish made from spinach

Xoyahusht: the name comes from the Juhuri words for "egg" and "meat," but it can also be prepared with fish and vegetables

Shomokufte: meat rolls popular in cold weather

You can also participate in a Mountain Jewish culinary masterclass here and learn to cook these dishes.

Another notable site in the village is the memorial plaque for Albert Agarunov. Born in Baku, Agarunov volunteered for the Azerbaijani Army during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1991 and served as a tank commander. On May 8, 1992, during the capture of Shusha, he was martyred by sniper fire while trying to rescue the bodies of his comrades. Both a mullah and a rabbi prayed at his funeral simultaneously. Agarunov was posthumously awarded the title "National Hero of Azerbaijan" in 1992. His brave life remains a symbol of Azerbaijani Jewish-Muslim brotherhood.

In the early 20th century, many rich houses and synagogues were designed by architect Hillel Ben-Hayyim, shaping the Red Village’s uniqueness. For example, the three-story mansion of the Aghababyev family, hidden behind half a teahouse on Fatali Khan Street, reflects the architectural style of that era. The residents spoke the Juhuri language and historically engaged in winemaking, tobacco and rose cultivation, and carpet weaving. Today, you can still see menorahs and dragon-motif Jewish carpets in local houses and museums.

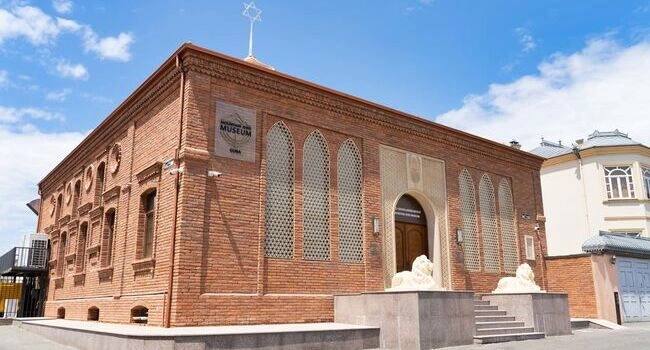

Of the 13 synagogues in the Red Village, only two are currently active, while a third has been restored for the Mountain Jews Museum. The museum is equipped with modern technology and introduces visitors to the rich history and culture of the community. It presents the long migration of Mountain Jews from the Middle East to the Caucasus, key traditions, crafts, and historical events through short documentaries, animations, archival photos, and interactive displays.

Tickets are available at the Information Center on Fatali Khan Street. From there, visitors can also arrange walking tours, hire guides, and enjoy coffee at the modern café.

Jews of Oghuz

Oghuz is a quiet and scenic town at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains. In addition to its interesting Jewish heritage, it hosts the Oghuz History and Ethnography Museum, located in one of the beautiful buildings of the Alban Church. The town also has a unique teahouse surrounded by forests, popular with local residents. Overall, Oghuz is an ideal place to rest and relax for travelers exploring Northwestern Azerbaijan.

Oghuz – Historical Jewish Footprints

Historically, Oghuz was one of the main Jewish settlements in the country. Mountain Jews and Muslims lived here in harmony, celebrating holidays and traditions together. Although many Jews left after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the old Jewish neighborhood still offers a fascinating view: Jewish-style houses (decorated with ornaments, often facing Jerusalem), two synagogues, and a cemetery complex reflect the city's Jewish past.

Oghuz Jewish Quarter

Locals call this neighborhood the "Cugutlar Quarter." Located in the southwest of the city, one of the synagogues here has historic monument status. Built in 1849, the two-story synagogue preserves traces of the city’s ancient Jewish community, while the other is relatively newer.

Mountain Jews with Tat-speaking heritage migrated to the Shaki Khanate in the second half of the 17th century. They lived in Zalam, Mucu villages, and the upper neighborhood of the district. Among Mountain Jews in Azerbaijan, those living in Oghuz call themselves Shekiyi, in Shamakhi Shirvoni, and in Quba Gubei.

Jewish Cemeteries

The newest Jewish cemetery in Oghuz was built in 1930 next to the old one, which has not been preserved. Early 20th-century social upheavals, religious oppression, and wars caused the old cemetery's destruction. Additionally, its hillside location, rain, floods, and tree roots displaced many tombstones, making it difficult to visit, although some stones remain visible.

The modern cemetery is open to visitors. Here, quiet narrow paths, old trees, and traditional Jewish tombstones – matzevot – allow learning about Mountain Jews’ history.

Synagogues

Two synagogues in the old Jewish quarter are called Upper and Lower.

Lower Synagogue (Arzu Aliyeva Street), built in 1849, is the first synagogue in Oghuz.

Upper Synagogue (Qudrat Atakishev Street), built in 1897 and fully restored in 2006, is visited for worship every Friday and Saturday by the small remaining Jewish community of Oghuz. Both synagogues are open all day.

Cuisine and Culinary Arts

The long-standing culture of Mountain Jews has greatly influenced their cuisine. These dishes vary from region to region:

Yarpagi: Famous in Quba, made with meat wrapped in cabbage leaves, cooked in plum sauce, and served with rice.

Oshyarpagi: Oghuz version, prepared similarly, steamed, topped with meat on bone, and served with rice and pumpkin slices.

Shitringe: Made with fried onions and eggplant, served with fried egg and rice.

Gireysu: A cold soup ideal for summer, made from fresh vegetables, herbs, and spices – cucumber, green onions, plum, garlic, served with raspberry juice and water.

Ismayilli – Basgal, Mucu Village

Although residents started leaving Mucu village in the 1860s, after the 1918 unrest, no one remained. Due to Armenian attacks, villagers had to flee to different parts of the country.

During this period, the village's Jewish cemetery was destroyed. Only a few tombstones from the 1910s remain today.

Currently, the cemetery has been restored, cleaned, and fenced. On a small stone platform, small tombstones are displayed. When funds were insufficient, small stones were raised, later replaced with larger ones when possible.

Famous Azerbaijani Jews

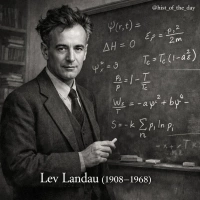

Azerbaijan, from the medieval historian and statesman Rashid al-Din to the country’s only Nobel Prize laureate Lev Landau, has been home to many world-renowned Jews. Here, we present some notable Jews born in Azerbaijan who made valuable contributions to science, history, and culture.

Lev Landau (1908–1968)

Lev Landau was an academic and one of the giants of 20th-century theoretical physics, as well as Azerbaijan’s only Nobel Prize laureate. Considered one of the USSR’s finest physicists, Landau became the first Baku-born Nobel laureate in 1962 and is undeniably a star in the history of the Baku Jewish community.

One of his contributions to theoretical physics was applying quantum theory to the motion of superfluid helium in 1941. He also introduced the concept of quasiparticles as equivalents of sound vibrations and vortices. Landau was a foreign member of the Royal Society (London), the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and an honorary member of the French Physical Society.

Young Landau demonstrated great talent in science from an early age and entered Baku State University at 14, studying physics and chemistry (later leaving chemistry). He then continued his academic career in Leningrad, Kharkov, and Moscow.

Gavriil Ilizarov (1921–1992)

Gavriil Ilizarov invented the Ilizarov apparatus and became famous for the “Ilizarov surgery” method named after him. He was the founder of a new movement in orthopedics and traumatology and transformed the approach to bone treatment in medicine.

Gavriil Ilizarov invented the Ilizarov apparatus and became famous for the “Ilizarov surgery” method named after him. He was the founder of a new movement in orthopedics and traumatology and transformed the approach to bone treatment in medicine.

Ilya Anisimov (1862–1928)

Ilya Anisimov was an engineer, ethnographer, and the first scholar of Mountain Jews. He authored the ethnographic book Mountain Jews of the Caucasus, published in 1888, which remains valuable to this day.

The Qusman Family

Suleyman Qusman (1904–1980) and his wife Lola Barsuk (1916–1977) were prominent members of Baku’s Jewish community. Suleyman served as a military doctor in the Caspian Fleet and during World War II, while Lola was a renowned linguist and researcher at the Institute of Foreign Languages. Their two sons – Yuli Qusman and Mikhail Qusman – became an award-winning film director and the first deputy director of TASS, respectively.

Suleyman Qusman (1904–1980) and his wife Lola Barsuk (1916–1977) were prominent members of Baku’s Jewish community. Suleyman served as a military doctor in the Caspian Fleet and during World War II, while Lola was a renowned linguist and researcher at the Institute of Foreign Languages. Their two sons – Yuli Qusman and Mikhail Qusman – became an award-winning film director and the first deputy director of TASS, respectively.

German Zakharyayev (1971–)

German Zakharyayev is an Azerbaijani businessman, public figure, philanthropist, and vice-president of the Russian Jewish Congress. He is also president of the STMEGI International Charity Foundation, promoting the history and cultural diversity of Mountain Jews, publishing books, and supporting diaspora communities.

German Zakharyayev is an Azerbaijani businessman, public figure, philanthropist, and vice-president of the Russian Jewish Congress. He is also president of the STMEGI International Charity Foundation, promoting the history and cultural diversity of Mountain Jews, publishing books, and supporting diaspora communities.

In 2014, Zakharyayev appealed to leading rabbis to recognize May 9 (26 Iyar in the Jewish calendar) as a

sacred day for Jews. This idea received broad support, and many Jewish communities worldwide officially celebrated it for the first time as a Day of Liberation and Freedom.